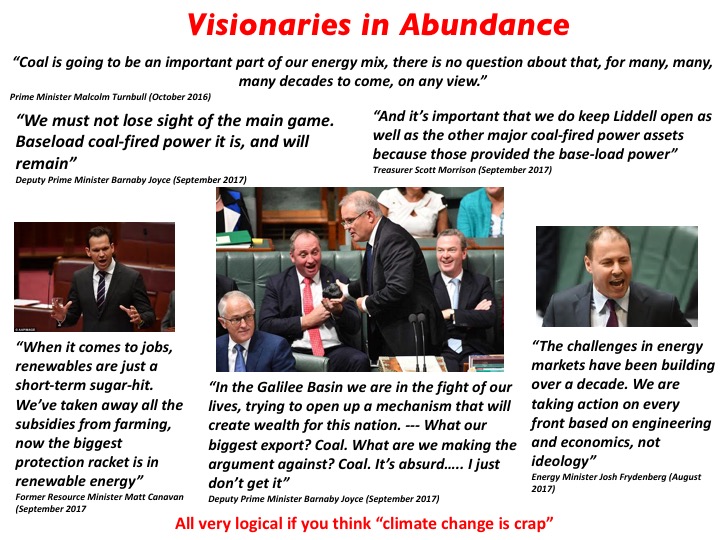

Energy policy is the issue to trump them all. We have already lost several Prime Ministers in its cause, and more will likely walk the plank before commonsense prevails. But the last few weeks have set new standards for national stupidity . The political rhetoric grows ever more florid, starting…

Category: Economics

The Leaders We Deserve ?

Rarely have politicians demonstrated their ignorance of the real risks and opportunities confronting Australia than with the recent utterances of Barnaby Joyce, Matt Canavan and other ministers promoting development of Adani and Galilee Basin coal generally, along with their petulant foot-stamping over Westpac’s decision to restrict funding to new coal…

Submission to the Review of Climate Change Policies 2017

Contents: Preamble The Key Issue – Existential Risk The Rapidly Changing Context of Global Climate Change Practical Implications The Australian Context Existential Risk Management Reframing Australia’s Climate Change & Energy Policies Author: Ian Dunlop Ian Dunlop has wide experience in energy resources, infrastructure, and international business, for many years…

Submission to the Finkel Review of the National Energy Market

Contents: Preamble The Key Issue – Existential Risk The Rapidly Changing Context of Global Climate Change Practical Implications The Australian Context Existential Risk Management Request to Expert Panel Preamble Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the Preliminary Report into the Future Security of the National Energy Market. …

Energy Security from Clean Coal, CCS & CSG – What could possibly go wrong ?

Every few years the fossil fuel industry pressures politicians to force “clean coal”, carbon capture and storage (CCS) and more recently coal seam gas (CSG) on an increasingly sceptical community to justify their continued expansion. This cycle started with promotion of Adani’s massive Carmichael coal mine in Queensland, for coal…

The Australian Elites Have Failed Us On Climate Change

The recent utterances of Maurice Newman, Chair of the Prime Minister’s Business Advisory Council, suggesting that climate change is nothing more than an attempt to establish “a new world order under the UN”, engendered some hilarity. They should not, because his comments highlight a fundamental failure of leadership on the…

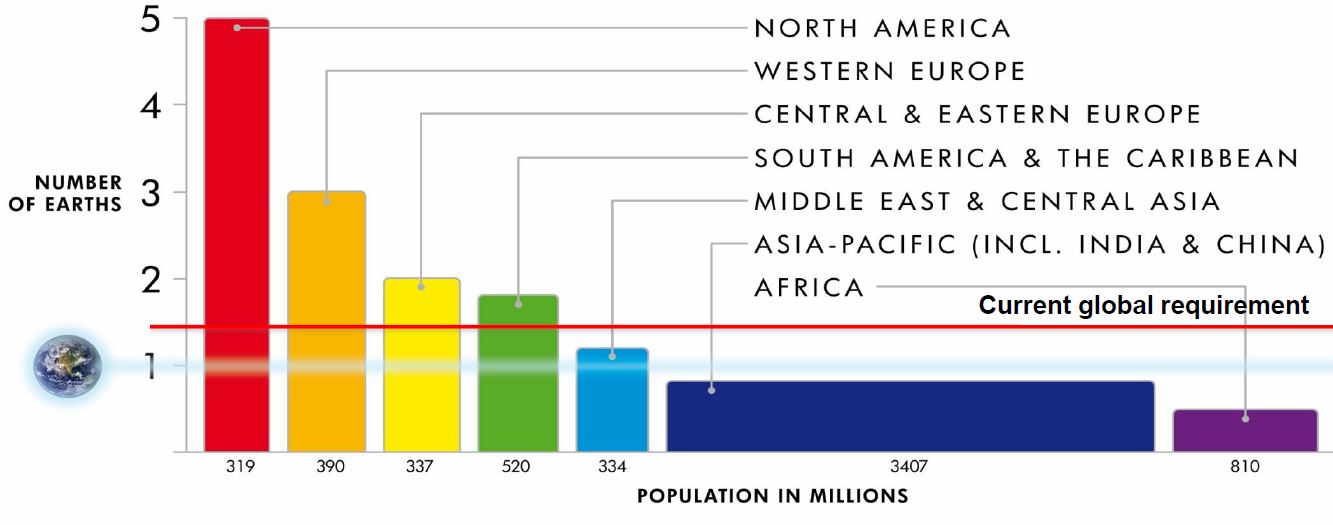

From Global Drivers to Strategic Risks

Since the Industrial Revolution the world has undergone an unprecedented transformation, largely a result of human activity. To the point, as proposed by Paul Crutzen, that we are now arguably in a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene 1, where humanity is the dominant force in world evolution. The changes…

Economic Crises and Their Impacts

Sean Costigan (http://www.gpia.info/node/357) interviews Ian Dunlop (http://cpd.org.au/user/iandunlop) on the economic crisis and its impacts on energy and the environment.