One of the few bright spots in an otherwise dismal global response to the escalating climate crisis has been the preparedness of financial market regulators to force their regulated institutions to face up to the implications of climate risk.

In so doing, they have been acutely aware of the lessons learnt from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, where scenario analysis, expert financial modelling and stress testing failed to foresee the crisis and the consequences for the banking system, investors and business alike. As a result, the global financial system was only save from collapse by a massive trillion-dollar bail out, for which the banks and corporations who caused it have yet to be held accountable.

When questioned by the Queen in 2008 as to why the crisis had occurred, the British Academy, after much introspection, responded that a “psychology of denial” led to “the failure of the collective imagination of many bright people … to understand the risks to the (financial) system as a whole.”

The reaction to the ominous warnings in the first part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 6th Assessment Report, recently released, demonstrates that the same psychology of denial is alive and well, particularly in Australia. The financial press has erupted with ever-more incredulous claims as to why gas, oil, and even coal are absolutely essential to solving the climate crisis. Politicians are suddenly experts in silver bullet technologies that will solve our problem without understanding the limitations of their claims, and trawl the web even more vigorously than normal for any sliver of denialist evidence that the climate issue might just go away.

Fortunately, regulators with independent mandates to ensure the stability of the global financial system are taking their responsibilities seriously. To make climate risks more transparent, central banks and regulators globally are stress-testing the financial system. Most notable have been initiatives by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the scenario work of the Network for the Greening of the Financial System (NGFS). In Australia, regulators have coordinated their work through the Council for Financial Regulators, with the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) initiating a climate vulnerability assessment for banks, encompassing scenarios up to 3°C of global mean warming, and issuing draft guidance for companies to stress test their own finances against scenarios up to 4°C warming.

Stress tests are simulations, relying on scenarios of future circumstances, and on models of the climate, the economy and the financial system. These techniques are valuable in reasonably well-understood circumstances, but they have severe limitations in addressing the threats which climate change now presents. The latest IPCC report has begun to discuss these issues, which include non-linear processes such as climate tipping points, cascade effects and radical uncertainty, where probabilities cannot be attached to specific outcomes, but even now the IPCC remain relatively reticent on these potentially existential, but increasingly possible, threats.

It is particularly challenging to map first-order physical climate warming impacts onto the second-order impacts in the social and financial spheres because it depends on the responses of complex human systems which cannot be reduced to probabilistic terms. In a complex world, systemic risks can arise from interactions between changes in the physical climate and human systems, so that small changes can lead to large divergences in the future state of human society.

Scenario analysis creates coherent, credible stories about alternative futures, allowing for constructive discussion on alternatives that should take into account the full range of credible evidence. But too often it is devalued and represents little more than sensitivities around some conventional strategic plan. Scenarios, properly used, can assist in securing a safe and stable future, but only if applied with brutal honesty in exploring extremes and not just a predetermined path.

Unfortunately global leaders, and Australia’s in particular, have not acted fast enough to avoid locking in extremely dangerous, and potentially catastrophic, climate impacts. Those impacts are close to moving beyond human control as global warming accelerates, evidence of which was clearly seen with the unprecedented 2019-20 Australian and Californian bushfires, the Chinese floods and Indian extreme temperatures. Even greater extremes are occurring in recent weeks in the Western USA, Canada, the Arctic, Siberia, Europe, China and the Amazon, resulting in some impacts that were not projected until around 2100.

In that context, the approach currently being used by regulators in assessing the future assumes compliance with the Paris Climate Agreement, unsustainable economic growth, a reliance on technologies not yet proven or deployed at scale, an overshoot of the Paris temperature target, and a big continuing role for gas. This worldview is being rapidly overtaken by events.

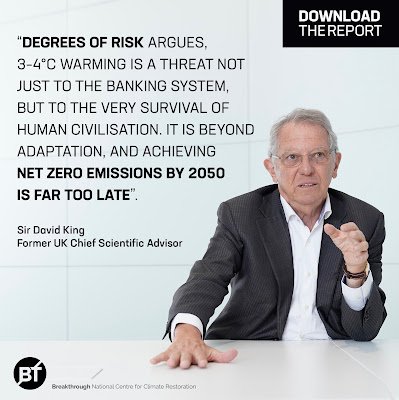

Scientists and analysts consider 4°C of warming to be an existential threat, incompatible with the maintenance of human civilisation, and 3°C to be catastrophic, perhaps leading to outright chaos in the relations between nations. Applying stress tests to such circumstances is problematic. Even at 3°C, the impacts may be so great as to be potentially infinite and unquantifiable, making scenario testing largely irrelevant.

It is unlikely that the banking system could survive such levels of warming, as discussed in our latest report: “Degrees of Risk: can the banking system survive climate warming of 3oC?”

Markets crave stability, but the world is entering an era of instability and uncertainty driven, inter alia, by climate-related financial risks. This makes the current approaches to managing these risks not fit-for-purpose. Sensible risk management, especially for highly uncertain events such as we are now facing, demands a precautionary approach, which must be applied to prevent these risks materialising.

Such precautionary action must ensure temperature outcomes do not trigger further tipping points or cascading effects which move the climate system beyond human influence, and are capable of returning it to the stable climate conditions under which human civilisation flourished. This means emergency action to keep the temperature increase to a minimum, as close to 1.5°C as possible, coupled with drawdown of current atmospheric carbon concentrations.

If the financial system is to survive and prosper, reactive disclosure of risks alone is no longer enough; time is short and mitigating those risks must become the absolute focus of regulators and regulated alike.

Company directors have a fiduciary responsibility to identify the risks to which their organisations are exposed, and to implement suitable systems to manage those risks. In the context of climate risk, boards of directors have too readily adopted recommendations from regulators and from supranational organisations such as the International Energy Agency or the IPCC, without bothering to understand the limitations of such analysis, thereby failing in their fiduciary responsibility to fully assess risk.

Regulators, here and overseas, exert great influence over financial and corporate players. If climate risk regulators imply warming of 3-4oC is manageable or can be adapted to, and such thinking becomes enshrined in the corporate psyche, as is currently happening, then regulators will be institutionalising failure, which is certainly not their intent.

Instead, regulators must now demand that the regulated proactively disclose what emergency precautionary action they are taking to ensure the world remains as close to a 1.5oC global mean temperature increase as possible.

This is just one change amongst many that must occur if humanity is to survive and prosper through the 21st Century and beyond. And it is an important one, because we cannot afford another failure of imagination.

Ian Dunlop is Chair, Advisory Board, Breakthrough National Centre for Climate Restoration.

David Spratt is Research Director of Breakthrough.

This article was published in Pearls & Irritations on 17th August 2021