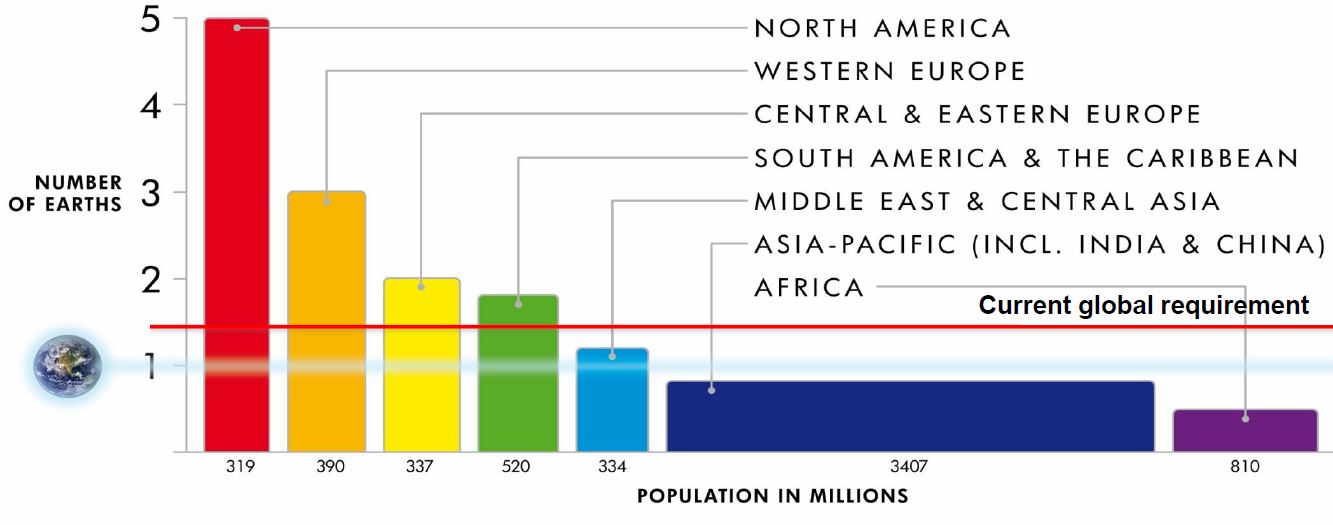

Since the Industrial Revolution the world has undergone an unprecedented transformation, largely a result of human activity. To the point, as proposed by Paul Crutzen, that we are now arguably in a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene 1, where humanity is the dominant force in world evolution. The changes…

Year: 2012

Climate Change

Continue Reading

Implications of Arctic Permafrost Thaw

Of the many “Elephants in the Room” in the climate change debate, none are larger than the potential release to atmosphere of carbon dioxide and methane contained in the Arctic permafrost. Preliminary findings from the latest research, discussed at the American Geophysical Union’s (AGU) annual conference in San Francisco in…

Realism needed on Carbon Capture and Storage

Sequestering say 20% of current global CO2 emissions requires an industry around 170% the size of the world oil industry. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) may make a significant contribution to addressing climate change, but: not in the short term, to prevent atmospheric carbon concentrations above 450ppm CO2e not at…